Context

The primary research was conducted at St. George’s Schools in a Grade 11 Social Studies class with parallel research being conducted at Crofton House School in a World History AP class. While some of the specifics of each location were different, the basic assignments were run in parallel. The St. George's side of the research is the primary focus of this site, but some comparison with the parallel Crofton House project will be made.

At St. George's, ⅓ students in each term wrote essays as the final product of their research and others created some sort of project. The type of project was left entirely up to the student. This assignment was repeated each term allowing each student the opportunity to write one essay and create two projects. Within the context of a broad topic or question (Canada’s involvement in World War II, Social Activism in the 1960s), the students were free to define the specific focus of their research. The teacher librarian worked closely with the subject teacher involved in the study, Stephen Ziff, in terms of teaching, assessment, data collection and analysis. The number of defined research participants at St. George’s represented approximately ⅓ of total class enrollment and volunteered to participate in the study. Due broader action research timelines, data was collected in the first two terms.

Process

assess the nature of student thinking through the inquiry and making process, qualitative data collection methods were primarily used. While it would have been nice to have conducted a more longitudinal study that compared summative assessments across groups, the time frame of the research did not allow for this. Ideally, we would have compared exam results for one group that had only produced traditional essays as the product of research units with a subsequent year in which made projects were produced. This data may be available from the Social Studies 11 exam after it is marked in the summer, and may cast a different light on our findings when we have it.

The qualitative data collection methods included learning logs, final assignment products, project proposals, interviews, surveys, informal discussions, group reflections, and student presentations. Data was collected throughout the inquiry process and teachers reflected on the process through a multitiude of formal and informal, individual and group exchanges.

While analysis and reflection on the data collected started as soon as data started coming in, the primary mode of analysis was to transcribe key quotes and ideas from the data collected on index cards and larger observations and reflections in a journal. The index cards were then re-sorted in a number of ways to identify similarities and contradictions in concepts emerging from the data. The most productive categories identified thinking around: curricular content, the research process, the making of the final product, time management, and other miscellaneous ideas. Reflection notes were balanced against the patterns that emerged from the categorization activity. After data was analyzed, conclusions were brought back to the participants in a full class discussion/debrief in order to ensure that the researchers’ conclusions rang true with the students.

Evaluation

At the end of the process, it was difficult to state that making, as an act, necessarily produced deeper thinking around an inquiry topic or that the thinking was necessarily different between a made product or a traditional written essay. Having said that, there were a number of observations made through the research that do impact how making might fit into the inquiry process.

First, making provides an opportunity for students to be able to think through their topics and tell their stories in different ways. Students tend to tailor their thinking to the type of product that they will be expected to generate at the end of the inquiry process. Essays tend to be focused on creating structured statements or arguing a particular point while ensuring that they reference the required number and types of sources asked for in the assignment. A student creating a text adventure game, for example, needs to think through a situation from a variety of positions in order to explore the topic fully. A visual or graphic artist might try to use symbolism and particular visual references, or principles of layout, design and organization of information to convey meaning. These types of outputs necessarily impact how a student thinks through and researches a topic.

There has to be a connection to the specific topic at the centre of the inquiry. While this has little to do with the end product of a line of inquiry, we saw, time and time again, that when a connection was made with a topic, the student was much more invested in the outcome of the inquiry. Greater investment equalled better work and deeper thinking. The comment that was made by some students was that when they were connected to a topic, typically the research would take much more time, simply because the student wanted to spend the time following up on questions that they needed to answer.

In our communities, writing essays is standard practice and much time is devoted to building essay writing skills. Whether students enjoy writing or not, they have learned the set of skills needed to write an essay. When faced with alternate forms of creating products that will share their new knowledge, many students struggle. They might try to find ways of writing an essay in a form that doesn’t look like an essay by building a text heavy slide presentation or website, or they may become debilitated by the process of making the decision in the first place.

It is crucial that the teacher considers what making skills a student may or may not have. If dictating the end product, as in a project- based learning scenario, a teacher needs to provide support, time and opportunities to learn the making skills required to be able to produce an object that tells the story of the student research. If leaving the the decision to the students, support may well be needed in helping students to inventory their current skills and finding the best mode for communicating their message. These are not decisions that come naturally to most. Even those that come to a project with a certain set of skills, they may be limited in their awareness of other opportunities to enhance their communication beyond the obvious. A board gamer might be able to design an amazing rule book for a well thought out game, but the physical production of the board and pieces may well lie beyond the skills that the student may need to take the game to the next level.

The placement of the decision regarding what form the final product will take is also important, but depends on many factors. Sometimes, there is great freedom in not thinking too much about the end product within the initial phases of inquiry. It is often better to allow students to truly explore a topic and develop a story before deciding on what the best way of telling that story is. Conversely, sometimes the act of making changes the research and thinking process, directing it down certain paths that wouldn’t be considered otherwise. If a particular way of thinking is desired, a particular made product may be the catalyst for that type of thinking.

Conclusion

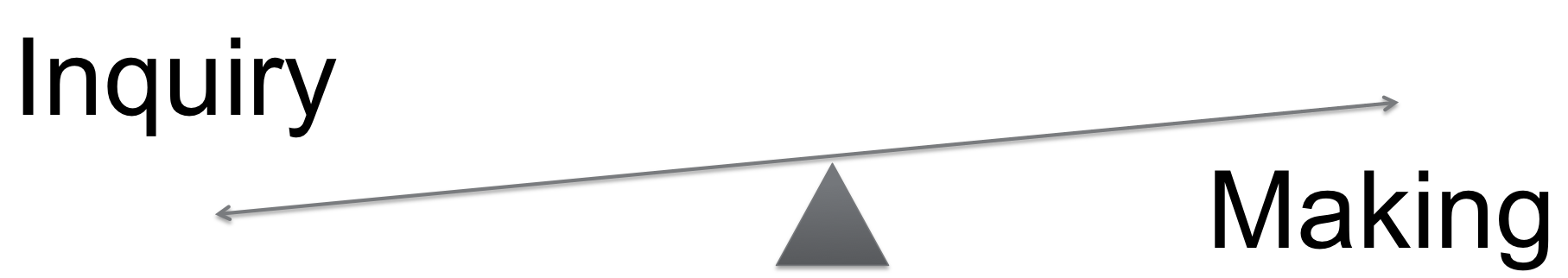

Making and Inquiry exist on a continuum. Emphasis may be put on either end of the continuum but they continue to support each other and are necessary for the success of each other. Our schools need to learn more about the benefits of and models for supporting maker or project-based learning while equally valuing and exploring new models of inquiry. We need to be mindful of how these opportunities are leveraged in our classrooms to affect the changes in learning that we are looking for.

Ways have to be found to scaffold students’ learning of making and inquiry skills both within a unit of study and across grades and disciplines in a school. We need to develop communities of practice that have well-thought out and communicated scope and sequences for teaching inquiry and maker skills so that we develop truly independent learners and makers by the time our student reach the senior grades. An organized approach to teaching these skills will allow for common vocabulary and expectations as to what students can do at any point in their growth. As independent schools we have a unique opportunity to think long-term about the growth of our students and this can only help the scaffolding required to reach our goals.

Finally, making needs to be seen as a transformative activity that not only allows a learner to share his new knowledge in more effective ways, but significantly changes his thinking about his learning as he works through his inquiry. We need to value these alternate modes of thinking and communicating as they are becoming more valued throughout society. As technology rapidly changes our social and work worlds, students have the opportunity to learn to go beyond telling people what they know to allowing them to experience what they have learned. Inquiry skills are essential to being able to figure out this rapidly changing world and making skills are similarly essential to being able to think and communicate more effectively.